“And to those of us who knew Mr. Emerson well, can you not even now see his twinkling eyes, hear his merry laugh, and his quaint exclamations…”

Charles A. Rich, 1918

Despite his deep associations with New England culture and architecture, William Ralph Emerson was born in Alton, Illinois on March 11, 1833. His parents – Dr. William S. Emerson and Olive L. Bourne – were natives of Kennebunk, Maine, but the family moved west as Dr. Emerson became involved in land speculation. Following her husband’s death in 1837, Olive Emerson and her two sons, Lincoln Fletcher (born in 1829) and William Ralph, returned to Kennebunk; a third child, George, died in Illinois as an infant. Olive Emerson married Ivory Lord of Kennebunk six years later, and his son Charles was likely the first architectural client of W. Ralph Emerson.

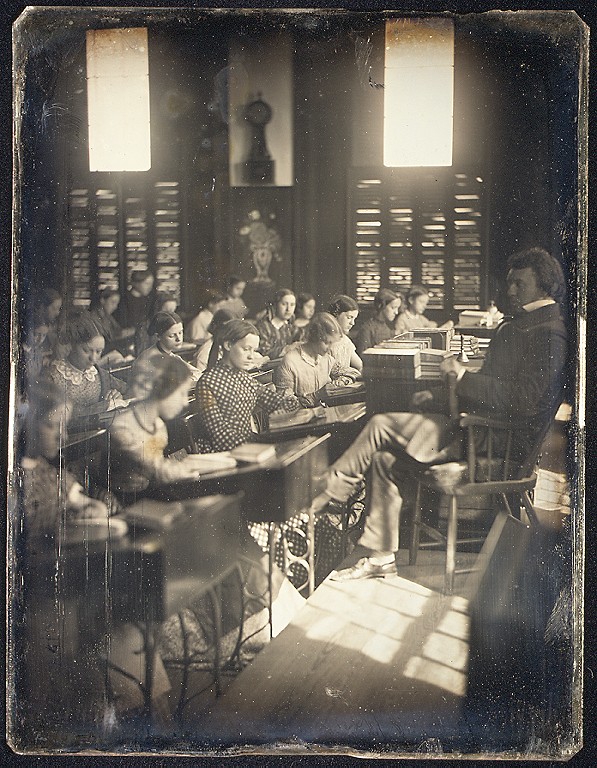

Lincoln and Ralph Emerson spent their childhoods between Kennebunk and Boston, where they stayed with their uncle, George Barrell Emerson. George Emerson was known in Boston as a writer, and also operated a well-regarded school for young women. Among those educated in Emerson’s school was Annie Adams, later Annie Fields – the partner of Sarah Orne Jewett – whose friendship with W. Ralph Emerson remained strong throughout her life.

Little is known of W. Ralph Emerson’s youth in Boston, but his brother attended Bowdoin College, and graduated in 1849. Though he spent time studying medicine, Lincoln Emerson followed in his uncle’s footsteps and went into teaching, but died young in 1864. Despite familial ties with several institutions, W. Ralph Emerson did not attend college. With no formal architectural school in America until 1868, Emerson’s only formal training likely consisted of time spent working in the Boston office of Jonathan Preston.

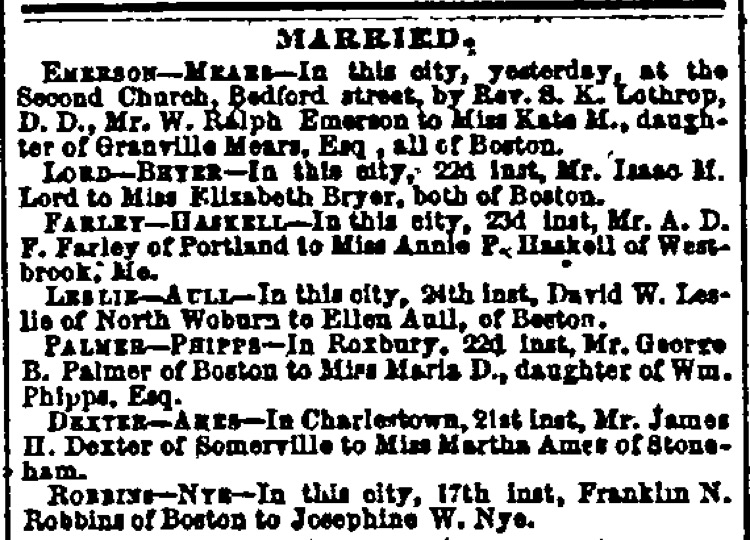

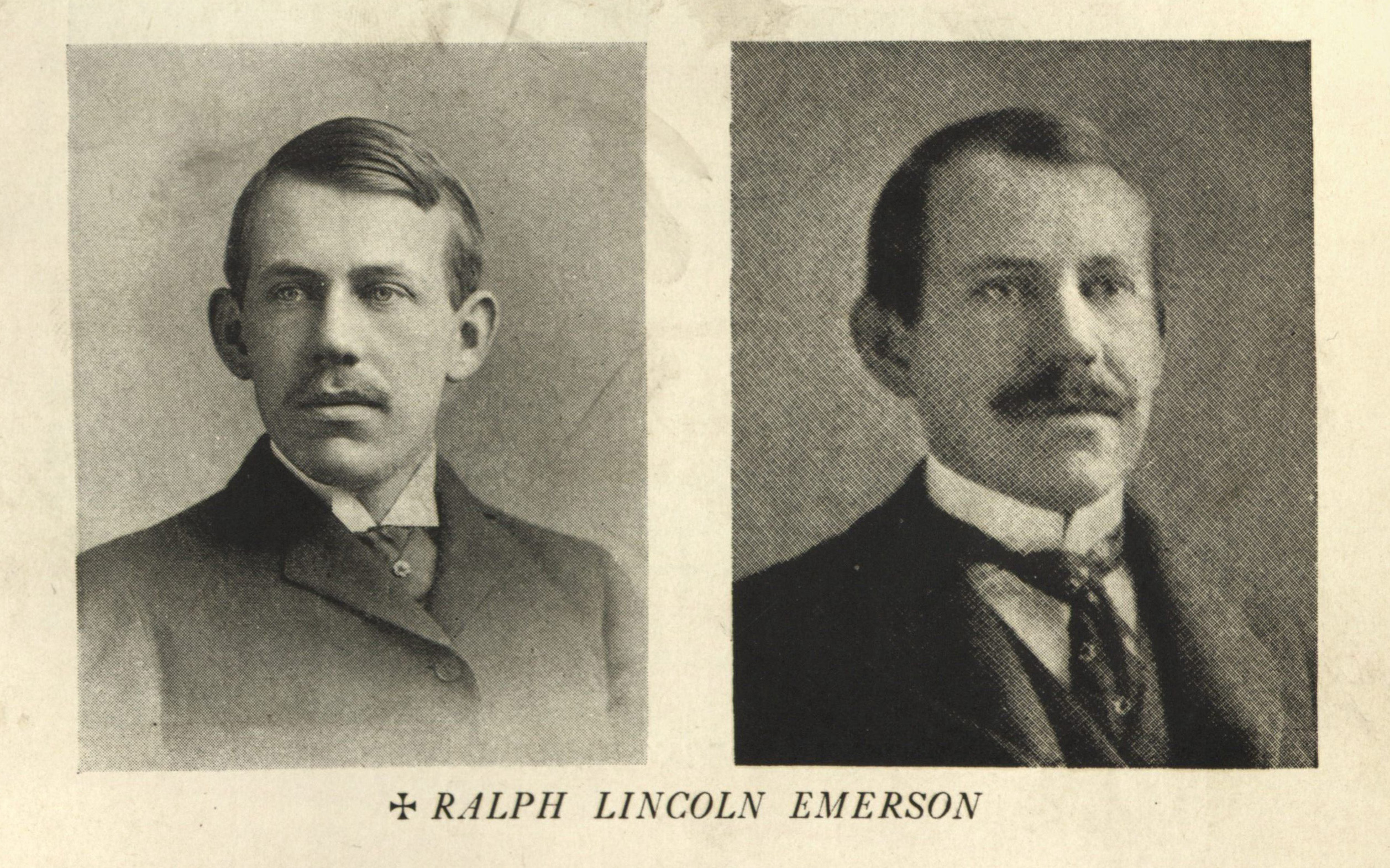

In addition to training as an architect, Emerson began his public lectures in the 1850s, and entered into politics as well. Starting in 1852, and continuing into the 1860s, W.R. Emerson served as a Ward Inspector, and involved himself in various political efforts in Boston. On December 25, 1863, he married Catherine M. Mears, known as Kate, in the Second Church, on Bedford Street in Boston. Moving to Braintree the couple welcomed their first child, a son, Ralph Lincoln Emerson – often called Rafe – in January 1868. Unfortunately Kate Emerson died three years later, at age 36.

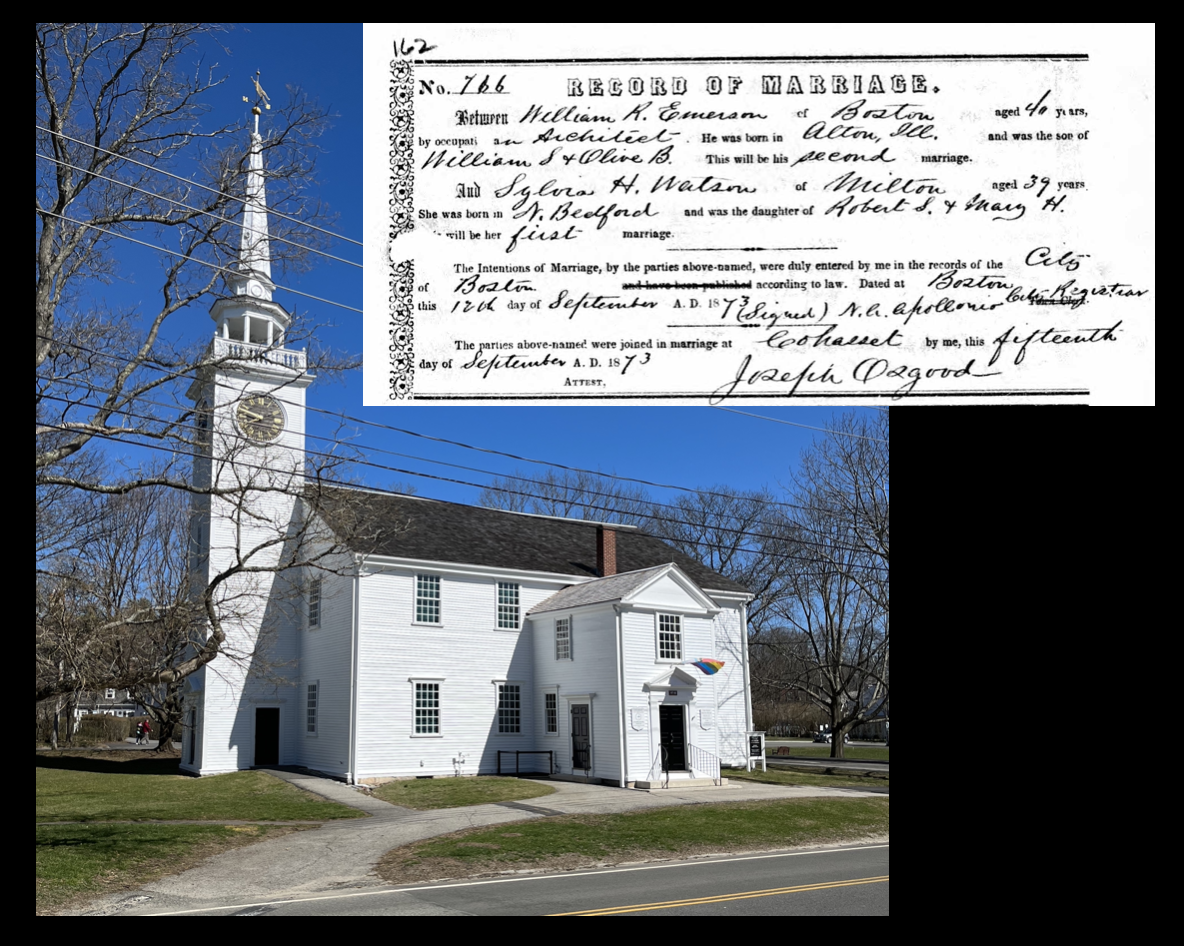

Around 1872, as he was planning and overseeing alterations to the house of Robert S. Watson in Milton, Ralph Emerson met Sylvia Hathaway Watson. The Watsons were well-connected in New England; they were related to the prominent Forbes family and were close friends with the family of Henry James. Writing to his brother, philosopher and psychologist William James, Henry James Jr. noted Sylvia Watson’s engagement to Ralph Emerson in June, and in September 1873 the couple married in Cohasset. A daughter, Mary Hathaway Emerson, was born the following year, but died as an infant.

Though they initially lived in Boston, the Emersons soon moved to Brookline, Massachusetts and, in 1886, to Milton, where W. Ralph Emerson designed a large, shingled house for the family’s occupancy. Like others of their social standing, the Emersons often traveled in the summer months. In the 1870s they spent time in Magnolia, Massachusetts, and it was on their invitation that the artist William Morris Hunt first came to the area, where he soon established a summer studio. The family also spent time on Naushon Island, where W. Ralph Emerson later carried out work for members of the Forbes family, as well as Marion and Hull in Massachusetts, Mount Desert Island, Maine, Newport, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire.

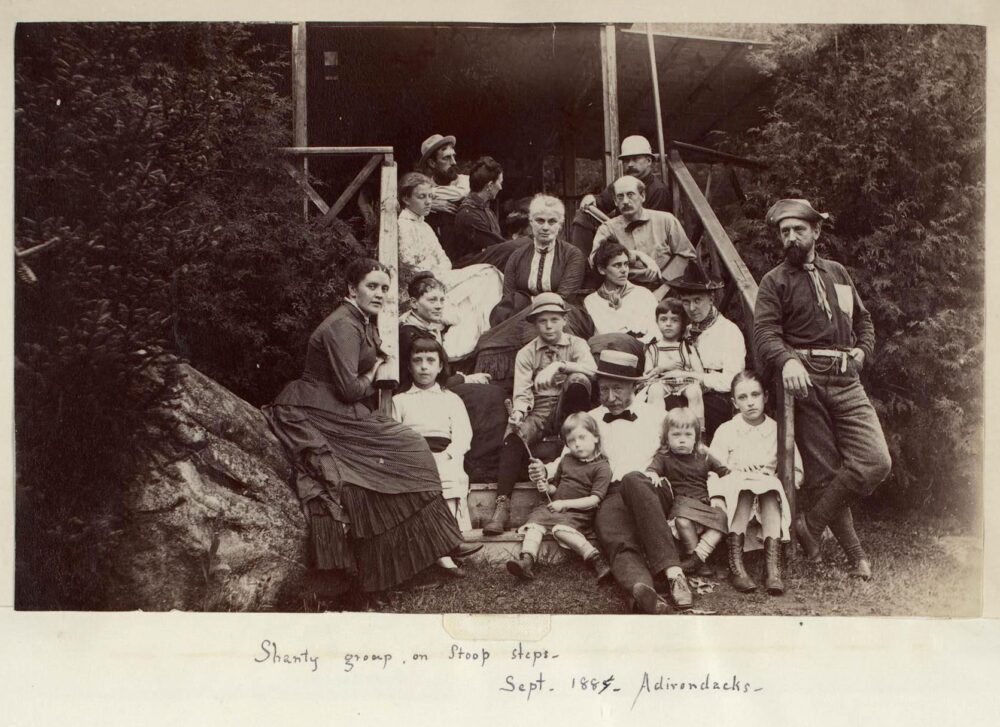

At times the Emersons joined other Boston families in the Adirondacks, staying at Putnam Camp in the Keene Valley region. Co-owned by several Bostonians, Putnam Camp was a compound of several buildings and guests enjoyed easy access to nearby trails and paths. Arriving in the Adirondacks in July 1884, Sarah Gooll Putnam noted in her journal that Mrs. Emerson and “Rafe” were already there and that “Mr. Wm. R. Emerson arrived on Wednesday the 23rd. He had a lovely time, walking, bathing in the brooks and sitting round the camp fire as usual at the shanty.”

By Sarah Gooll Putnam, Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Photographs show the Emersons enjoying their time in the mountains, whether reading outside or surrounded by friends and family. Then at the height of his architectural career, W. Ralph Emerson undoubtedly enjoyed these respites from busy office life. Rafe, a teenager at the time, enjoyed the beauty of his surroundings and recorded them photographically. Some of these photographs were later given to Sarah Putnam, who pasted them into her diary.

Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Unlike his father, Rafe Emerson attended Harvard and graduated with the class of 1891. He was involved in many student activities including The Harvard Lampoon, the Art Club, Hasty Pudding, and others. Following his graduation, he and his parents traveled to Europe, a trip that may have been W. Ralph Emerson’s only voyage abroad. Though their full itinerary remains unclear, the group arrived in Liverpool in the summer of 1891, and Charles Cogswell, a young Boston architect studying at the École des Beaux-arts, wrote to his parents of dinner plans with the Emersons in Paris that October: “I expect to have a queer time as he is such a ‘crank’ on a good many subjects connected with the profession,” Cogswell projected. In the winter the Emersons were in Italy, and spent time visiting cities including Rome and Assisi.

Though they lived in Milton, Ralph and Sylvia Emerson enjoyed Boston immensely and often spent winters in the city, occupying rented townhouses and enjoying easier access to friends and social events. Sylvia Emerson rented a painting studio and worked on portraits, while Ralph kept busy with his architectural work, speaking engagements, and professional clubs. “Ralph loves the very bricks of Boston,” Sylvia wrote to a friend in 1897, and in lectures he often discussed nearby buildings that provided him with constant inspiration. Though he involved himself in efforts to preserve older buildings, especially the Old South Meeting House, the Emersons witnessed Boston grow and modernize; Sylvia Emerson referred to early automobiles as “elephants on wheels.”

Rafe Emerson also settled in Boston, working in his father’s office and involving himself in area social groups. Continuing a college passion, he served as stage manager for plays put on at Copley Hall in 1896, and newspapers celebrated his efforts: “No small part of the success of the performances was due to the capable stage management of Mr. Ralph L. Emerson. His proficiency was no doubt due to former experience which he had as the designer of the scenery and as property man for the Hasty Pudding theatricals in 1891.”

Concerned by her stepson’a by delicate health, Sylvia Emerson worried about him in letters to friends, especially when sicknesses took hold of Boston during the winter months. In the fall of 1898 he became engaged to Lillias S. Stephenson of St. Paul, Minnesota, but poor health forced him to travel to south that winter. On April 14, 1899 Ralph L. Emerson married Lillias Stephenson, but he died the next day.

Lillias Stephenson returned to Milton, living and traveling with her in-laws for the rest of their lives. Though they had no surviving children, the Emerson house was busy and often full of young people. Sylvia Emerson’s nephew lived across the street, and his children spent a great deal of time with their older relatives. Named for Sylvia Emerson, Sylvia Watson remembered this time fondly:

“Aunt Syl was a rare and most unusual person, artistically extremely gifted, with a brilliant mind, and a great love of people. Children and young people adored her. Uncle Ralph was one of the most distinguished architects of his time… The studio ran across the entire west end of the house, and in it was an enormous table covered with Uncle Ralph’s plans and sketches, and Aunt Syl’s paintings and drawings. In one end of the studio was a swinging hammock, covered with coarse canvas or sailcloth. When Aunt Syl felt tired, she lay down on the hammock, gently rocking herself… In the studio there was a secret door in the paneling, and behind it a tiny staircase that led to the second floor. When Aunt Syl’s numerous relatives became too many, Uncle Ralph escaped through the secret door and up the staircase. The house had no formal living room… In Aunt Syl’s dining room was a large white china hen. The top half of the hen was the cover, and the bottom half was always filled with sugar cookies, to which we could help ourselves… For several months before she became really ill, Aunt Syl gave me a painting lesson once a week and I can remember my feeling of excitement and honor. She showed me how to paint a flower in water colors, and I can remember her doing a charming little Victorian flower painting of a Johnny-jump-up. Aunt Syl was highly individual and most unusual, and stands out vividly in my memory as a very special person.”

“Gift of W.R.Emerson estate. May 1923” written on back

Courtesy of the Boston Athenæum

In June 1917 Sylvia Emerson died at home, followed on November 23 by her husband, and both were buried at Forest Hills Cemetery. Lillias Emerson remained in Milton, moving into another house designed by her father-in-law. To see a photograph of Lillias Emerson, click here. It is not clear whether any of Emerson’s office files remained at the time of his death, but some of his architectural photographs were given to the Boston Athenæum in the years that followed, providing an idea of what may have once existed in his professional files.

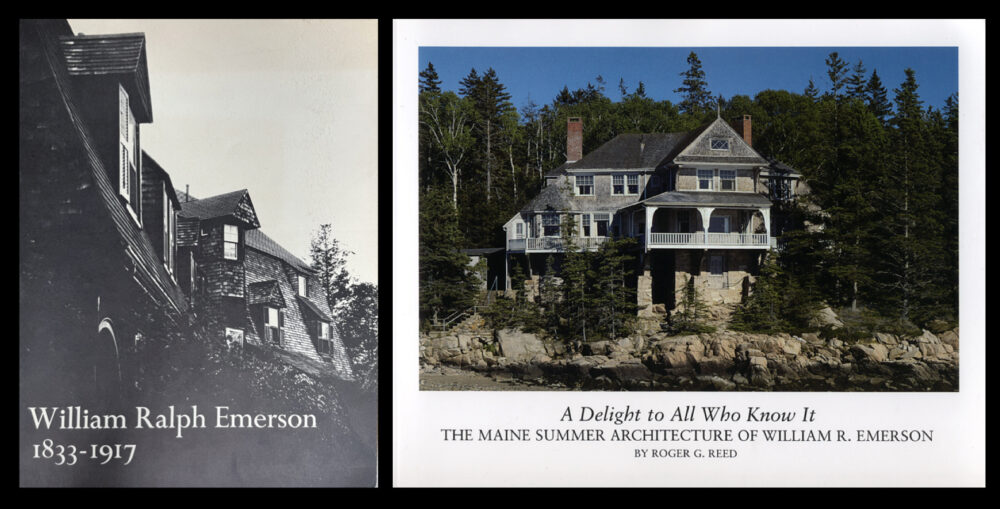

Though interest in W. Ralph Emerson waned in the years after his death, scholars understood his importance in the evolution of American architecture. Writing in 1941 for The Art Quarterly, Roger Hale Newton underscored the importance of those he called “The Boston school of architects”, noting that they “shone with considerable brilliance in supplying Classical themes drawn from their Colonial heritage. William Ralph Emerson early led (sic) this field at Bar Harbor.” In his Yale dissertation, which was revised and published in 1955, Vincent Scully also noted the central role of William Ralph Emerson in the development of American architecture. Emerson’s design for C.J. Morrill in Bar Harbor was, Scully claimed, “the first fully developed monument of the new shingle style.”

Though these earlier scholars recognized his talents, they did not focus solely on Emerson or his work. It was not until 1969, when Cynthia Zaitzevsky mounted an exhibit at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum, that William Ralph Emerson was celebrated as an individual. Zaitzevsky’s exhibit brought together drawings by Emerson and photographs by Myron Miller, presenting visitors with a nuanced understanding of Emerson’s houses and their architectural features. In addition producing a biographical essay, Cynthia Zaitzevsky compiled the first catalogue raisonné, which identified 80 buildings. Building on the work of Dr. Zaitzevsky, Roger Reed’s book A Delight to All Who Know It: The Maine Summer Architecture of William R. Emerson (1990, rev. 1995) provided new insight into Emerson’s career, detailed descriptions of his work in Maine, and an updated catalogue raisonné with nearly 200 entries. David W. Granston III built upon this previous scholarship and, with the support of Historic New England, had an opportunity for more focused study. With this website, Willie is able to sharing much of this information with others.

revised 10 November 2023