Emerson, although an architect of great talent, was a painter by nature and his pictures made one forget everything else in the bewitching effect of the rich harmony of color.

Francis S. Swales, 1925

Though he was an architect by trade, William Ralph Emerson’s reputation as an artist was well-known in New England and beyond. Like his architectural designs, Emerson’s artworks show his interest in studying and understanding his surroundings – both urban and rural – and his efforts to shape effects through color and light. He was not the only artistic member of his immediate family, however. Sylvia Emerson, his second wife, studied painting as a teenager and, as an adult, was known for her portraits. Emerson’s son, known as Rafe, was a member of the Art Club during his time at Harvard, and took part in life-drawing classes as a young man. Though only a small number of original artworks have been located, newspaper articles, written descriptions, and period images provide insight into this important part of the Emersons’ lives.

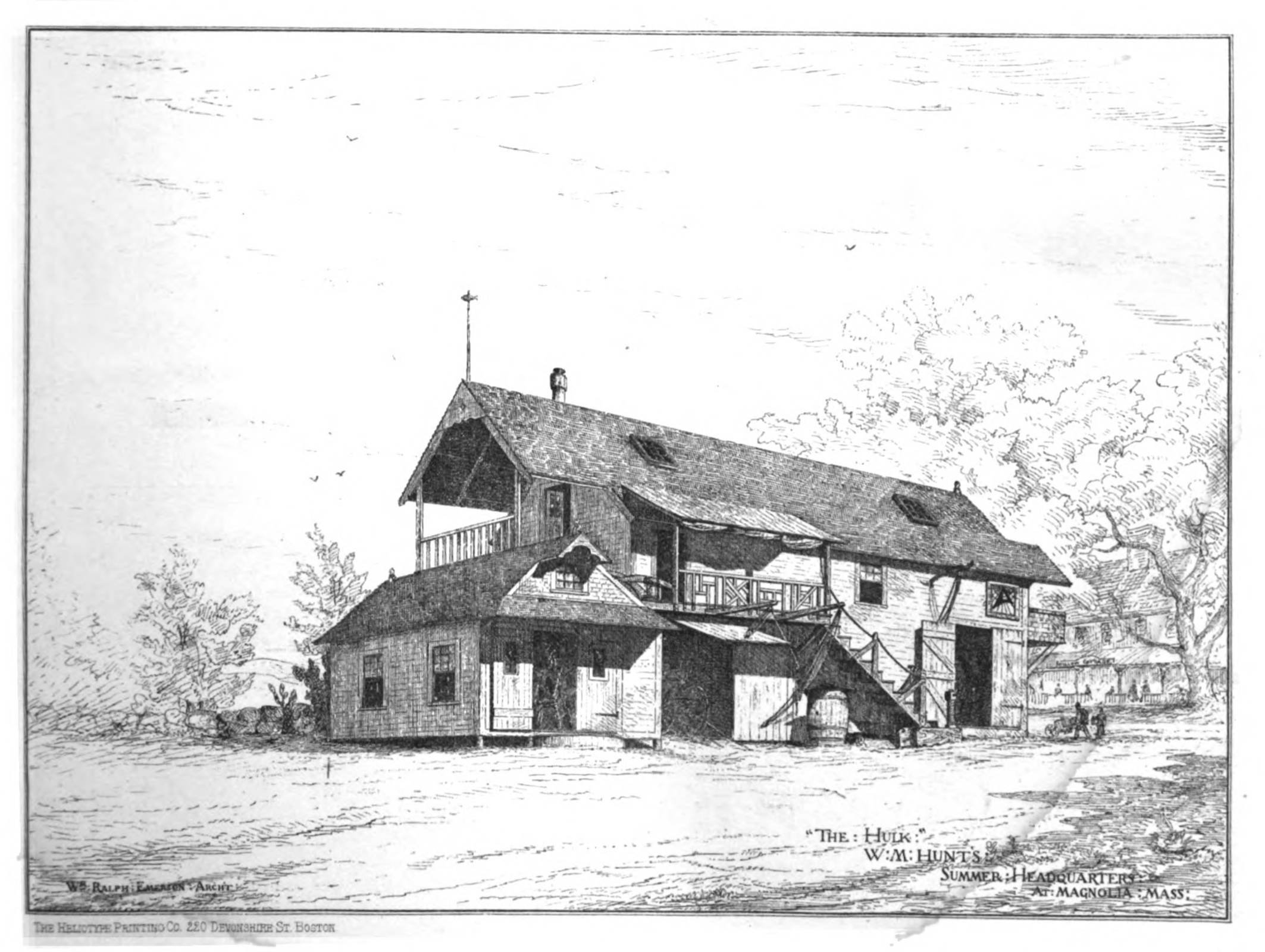

In 1860 William Ralph Emerson entered Boston’s artistic scene by joining the Boston Art Club. Founded in 1855, the club fostered camaraderie among those involved in the fine arts by providing art classes and hosting exhibitions. These activities clearly interested the young architect, and in 1866 “Mr. Ralph Emerson”, then president of the Boston Art Club, oversaw the installation and opening of an exhibit held in Boston’s Horticultural Hall. The event was popular and well-attended. Newspapers celebrated the “brilliant display of several hundred pictures, the work mostly of our resident artists,” and noted that “Large numbers of our fashionable and wealthy citizens were present… a succession of carriages rolled up to the door for an hour or two.”

The Boston Art Club remained an important part of Emerson’s life. His architectural drawings were included in several of the club’s exhibitions, and in 1880 he was selected to design the club’s new Back Bay headquarters, which still stands today on the corner of Newbury and Dartmouth Streets.

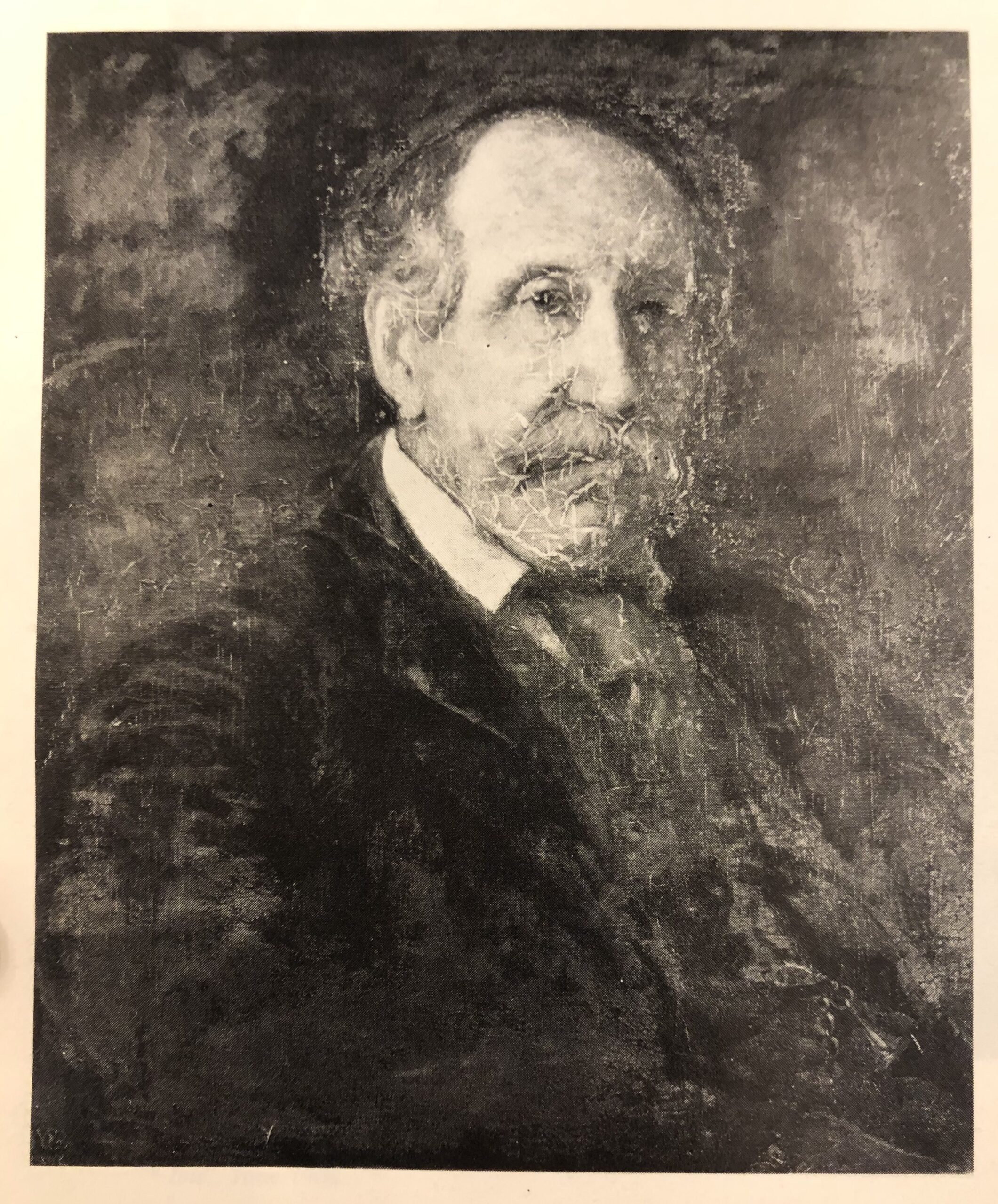

Courtesy of Historic New England

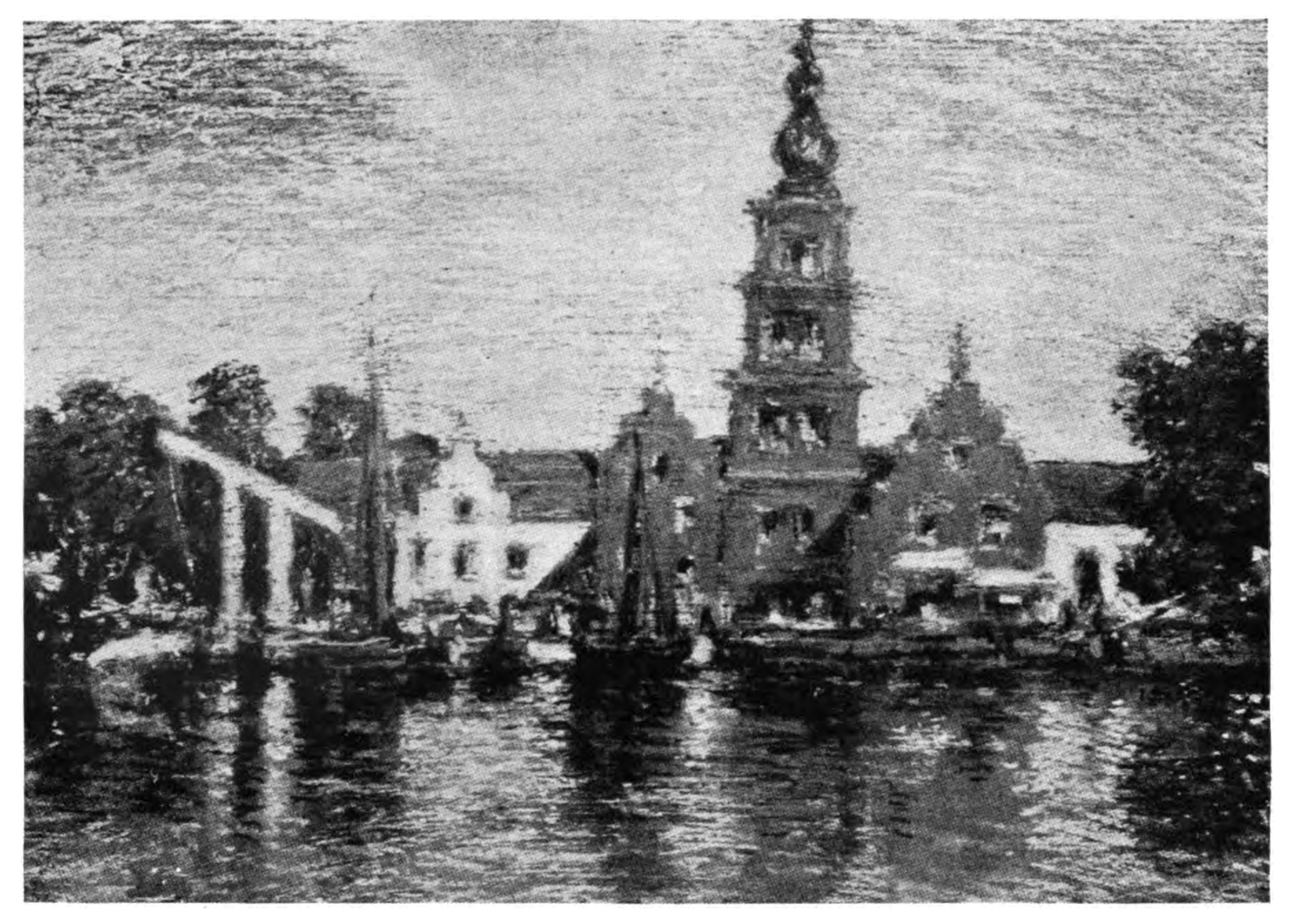

Emerson’s involvement in New England’s artistic endeavors likely introduced him to many of the region’s prominent artists, and over the course of his career he designed and oversaw construction of at least three artists’ studios. The first of these, and most imaginative, was that designed for William Morris Hunt, a noted portrait and landscape painter, and close friend of the Emerson family. Hunt painted a portrait Emerson’s son, Ralph L., as child, and in 1877 visited Magnolia, a summer community on Boston’s North Shore, at the invitation of his architect friend.

Enjoying the scenery and climate, Hunt asked Emerson to help him with the design of a summer studio and residence. Converting an old barn and connecting it with a workshop building, the finished structure, with oddly-shaped exterior, was called The Hulk. Adding interest and whimsy, Emerson’s design included stairs that could be raised and lowered like gangways, a newel post made from a cider mill screw, and railings and braces created from whale ribs and vertebrae. Across the front of an especially low balcony, Emerson himself painted a decorative warning: “Men that are tall keep near the wall.”

Emerson’s familiarity with Hunt may have resulted from his wife, Sylvia, who studied under William Morris Hunt and was, herself, an accomplished painter. In letters Sylvia Emerson often described the works then in progress in her studio. Writing from Boston in December, 1896, she told one friend, “I am painting 6 hours a day and at present I am working on the portraits of 2 of Judge Lowell’s grandchildren at Chestnut Hill 3 days of the week. The other three I am going to paint a friend of Ralph’s who is the Pres[ident] of the architect’s society.” Upon its completion the portrait of Edward Clark Cabot was hung in the Museum of Fine Arts and, more recently, at the Boston Public Library.

Owned by the Boston Architectural Club, hung at the Boston Public Library.

Photograph by Richard Cheek, included in The Magazine Antiques, November 1978

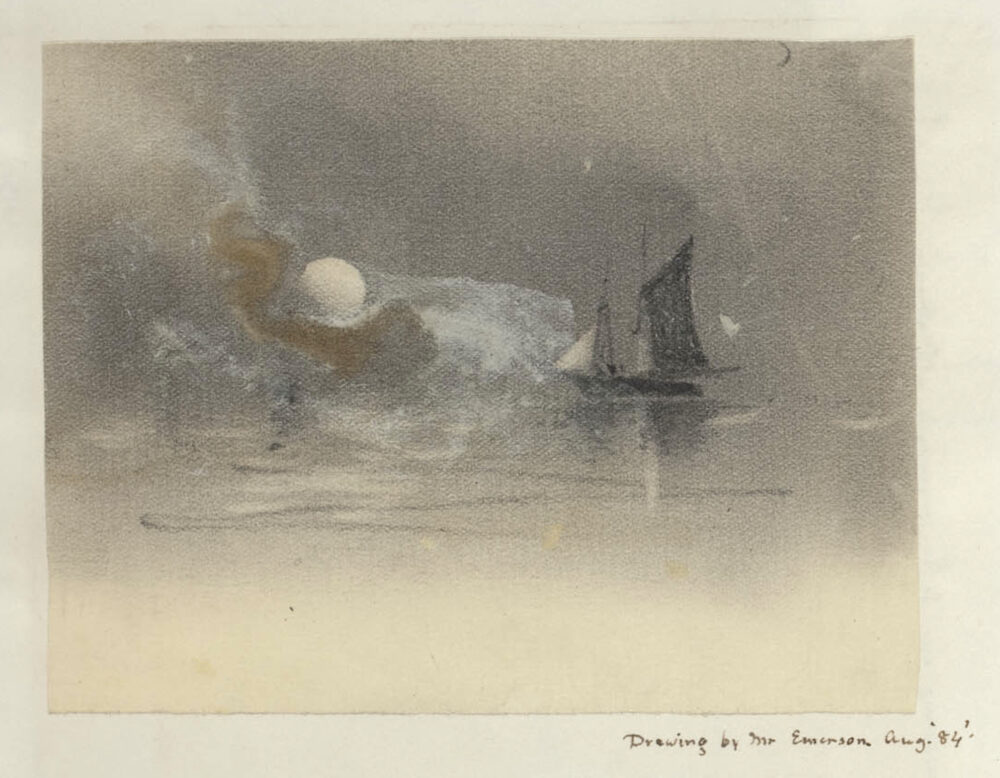

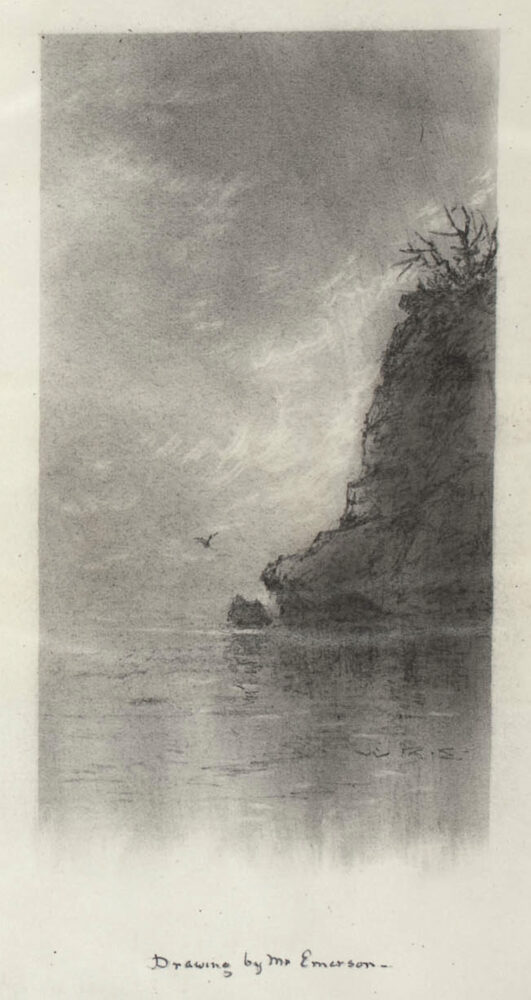

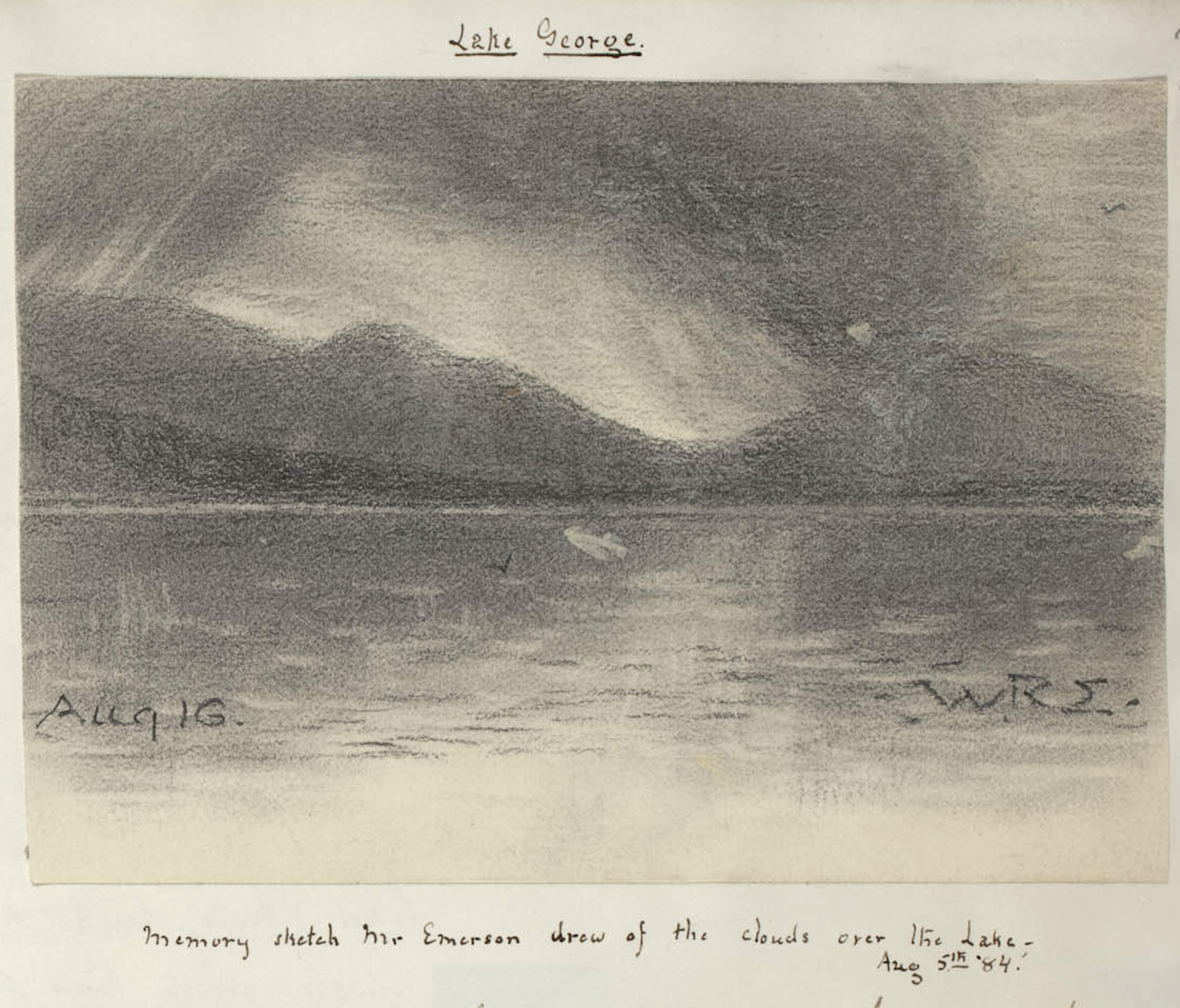

The Emersons were close with other area artists including Anne Whitney, a Boston sculptor who gave the architect a bust of the poet John Keats, and the family often encountered artist friends at social events and while traveling. To read a letter from Emerson to Miss Whitney, click here. In August of 1884, W. Ralph Emerson traveled to Nahant and spent time with artist Sarah Gooll Putnam, a Boston artist and the sister of architect John Pickering Putnam. Over the course of several days, Emerson and Putnam spent time enjoying the area landscapes, and Sarah Putnam pasted several small drawings by W. Ralph Emerson into her diary. “He and I went sketching, and he drew any number of pencil dust pictures like the one on the opposite page,” she wrote in one entry.

Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

included in the Diaries of Sarah Gooll Putnam, collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

A whimsical seascape, with a schooner lazily sailing among fogbanks, Emerson’s “pencil dust picture” was dramatic and moody. In other drawings saved by Putnam and glued into her diary, Emerson recorded landscape scenes of the North Shore, including one of a rocky headland, the ominous cliffs accentuated by brighter clouds. Another, completed during the architect’s visit to Nahant, offered a “memory sketch” of Lake George, New York, an area visited by Putnam and Emerson during a trip to the Adirondacks earlier that summer.

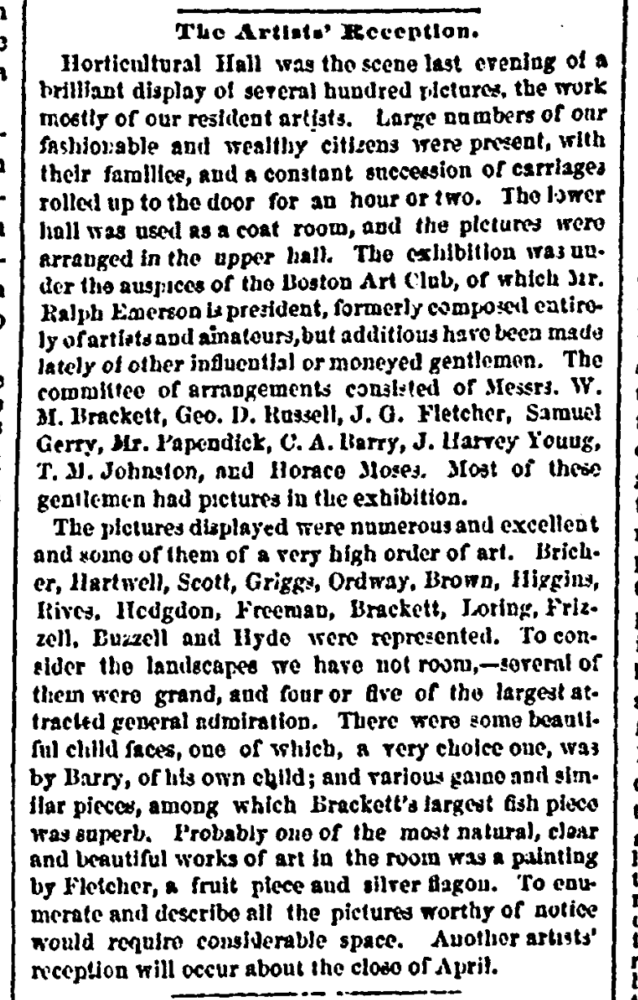

Emerson’s loose drawing style attracted the interest of artists, architects, collectors, and reporters. Willing to experiment, he found artistic potential in unconventional materials such as shingles instead of paper, and carpenter’s chalks, used to mark boards, instead of colored pencils or crayons. Pastel like Old Dutch Town were exhibited as far away as Detroit, and even after Emerson’s death in 1917 the work of art continued to attract attention. Writing in 1925, Francis Swales illustrated and discussed the decades-old artwork in an article on freehand drawing. It was, Swales wrote, “drawn in pastels of rich colors on a shingle, the grain of which was utilized in the indication of sky and water while the pastel was pressed into the wood to give solid effect to the buildings.”

As his architectural practice slowed, W. Ralph Emerson appears to have devoted more time to his artwork. In 1904 an exhibition of Emerson’s “chalk drawings” opened at Walter Rowland’s Boylston Street, Boston gallery. Described by the city’s newspapers, Emerson’s artwork obtained widespread notoriety. “These are much more than mere ‘chalk drawings,” claimed The Boston Globe; “they are, many of them, exquisite pastels, rich in color and in architectural effects and in poetical imaginative nature.” Though they were imagined scenes of European towns, “impressions gathered here and there in the world,” as one journalist wrote, these pictures were well received. Like his architectural designs, these pastel drawings were imaginative and inventive, combining Emerson’s talents with his creative spirit. Reminiscent of Impressionist art that he likely saw during his 1891 trip to Europe, Emerson’s pastel scenes are often loosely rendered and his layering of colors creates complex artistic effects.

Following his death in 1918 several obituaries and eulogies included references to his skills as an artist. As the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association wrote of their fellow member, “Mr. Emerson was a painter as well as an architect; pastel was his favorite medium, but he loved to experiment, and the many pictures he left behind testify to his talent and skill. Many people will remember his remarkable ability to draw with both hands.”

revised 10 November 2023