Between Quincy and Milton we pass several of Mr. Emerson’s delightful houses. He builds with the idea of making the house a natural part of the landscape… Mr. Emerson wants only a large, wide-spreading elm tree, plenty of ground and carté [sic] blanche, then like the magician, he clasps his hands, whispers presto, and behold the little red cottage, nestling in the shadow of the far-reaching branches, or by the old rail fence with his yellow shingles he builds his characteristic house, and we loiter by the way in admiration.

Frank E. Wallis, “Wheel Sketches” Building, October 6, 1888

Writing for readers of Building, a late nineteenth-century architectural periodical, Frank E. Wallis described a trip in which he and a group of friends mounted their bicycles and went to study buildings in the towns surrounding Boston. To record their impressions of these sites, the travelers brought their sketchbooks and spent hours drawing architectural elements and features that caught their interest. Returning to Boston by way of Milton, the group passed a number of buildings designed by W. Ralph Emerson and stopped to admire them. By 1888 Emerson’s reputation as an innovative architect was well known, and young professionals like Wallis and his friends would have been familiar with his designs, which often appeared in magazines and exhibitions. Eager to increase their architectural awareness, young architects went to observe and study these buildings firsthand, and many attended lectures and discussions led by Emerson, who took personal interest in teaching helping a new generation of design professionals.

Emerson often hired younger architects as draftsmen and, given the close-knit nature of Boston’s architectural community, mentored individuals employed in other firms as well. As a young architect working from an office in Pemberton Square, John Calvin Stevens became close with Emerson and his office staff. Though Fassett & Stevens was a competing firm, Stevens became familiar with the work and ideas coming from the Emerson office, and learned many lessons from them. Recalling those years later in his life, Stevens wrote: “I can never forget the friendly manner and interest displayed by William R. Emerson whose work and words were an inspiration. His office was in the same building and the fine fellows in that office took me in as almost one of themselves.”

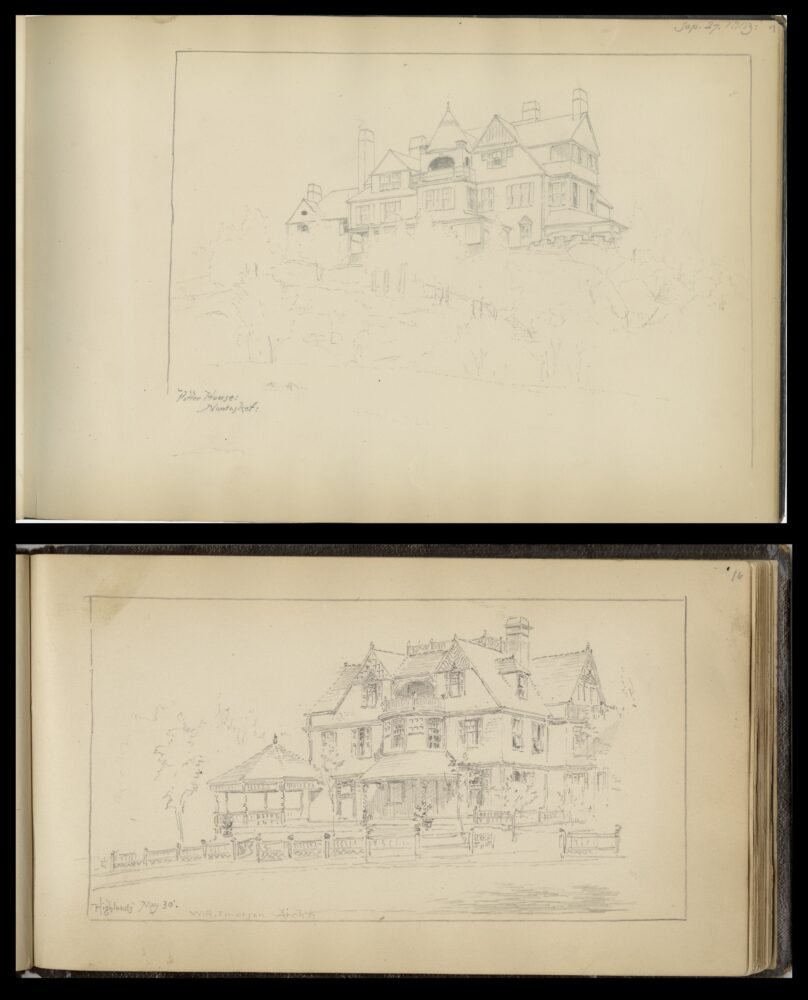

In travels around New England, Stevens looked for Emerson buildings and took the time to sketch them, not unlike Frank Wallis and his friends. Stevens located Emerson’s work in Maine and Massachusetts, and in his drawings showed an appreciation for the forms, details, and relationships between the designs and their surroundings.

Like Stevens, R. Clipston Sturgis also took the time to locate and study Emerson buildings, and his drawing of the Mary Hemenway House in Manchester by-the-Sea provides a detailed view of the North Shore summer residence owned by Edith Eustis’ mother.

Memorial Library, Boston Architectural College

For those unable to visit these places firsthand, commercial enterprises like The Soule Photographic Art Company sold professionally produced photographs. Demonstrating a widespread interest and a desire to see and study Emerson’s buildings and their interiors, the images produced by Soule and other photographers allowed individuals to visualize and appreciate the work of W. Ralph Emerson regardless of their location.

Soule Photographic Art Company Photograph, courtesy of Historic New England

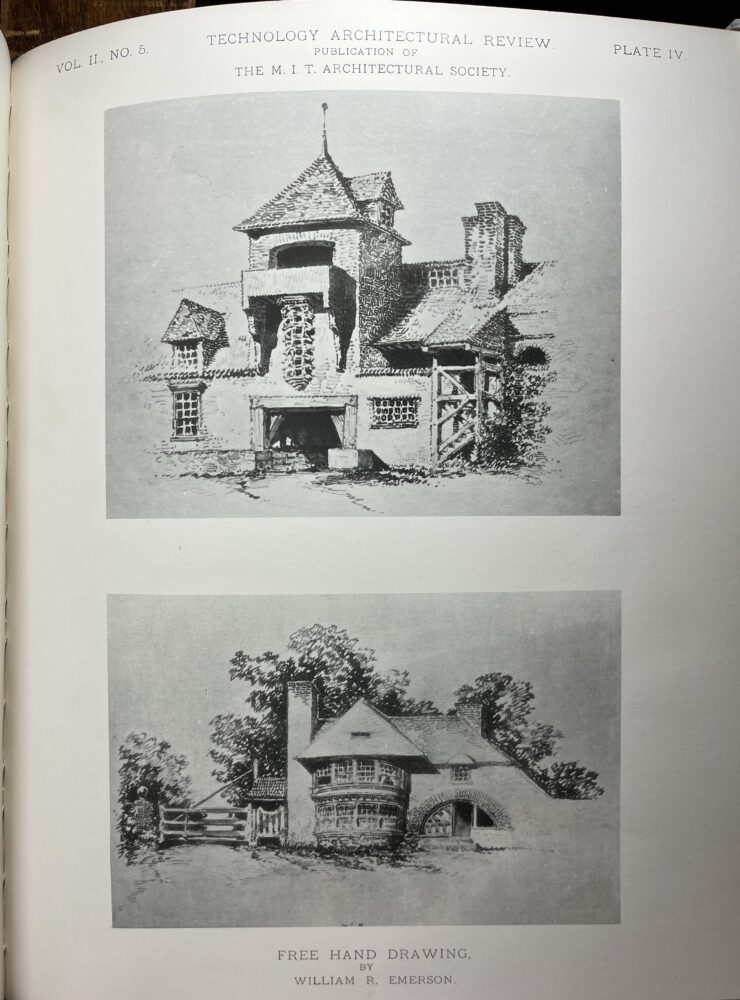

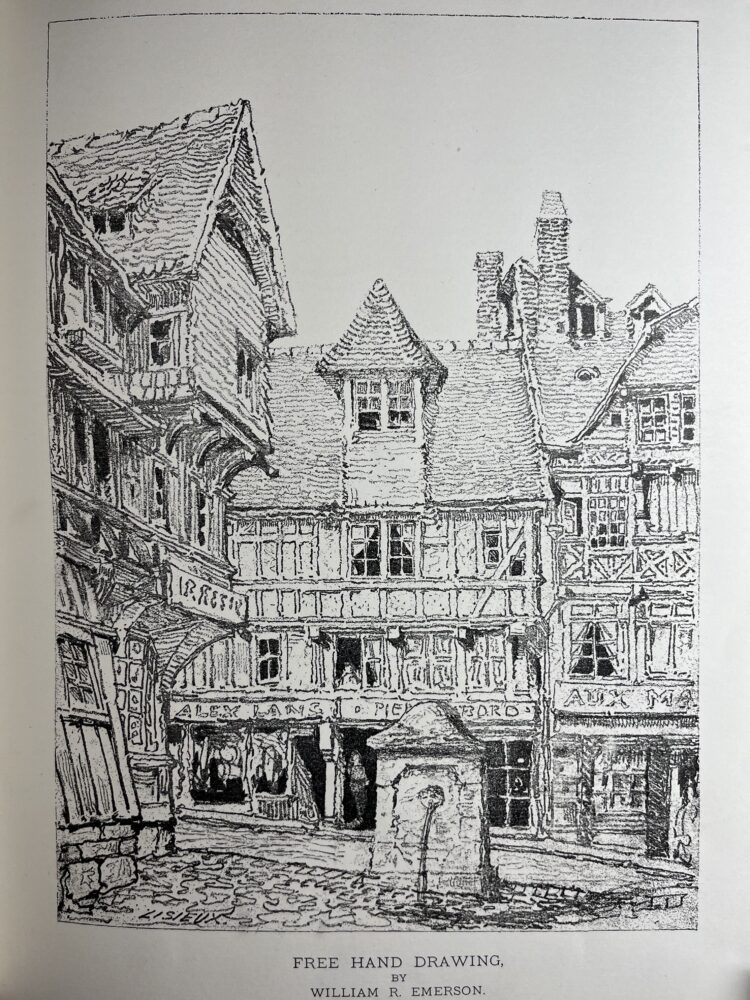

Emerson took a great deal of interest in spreading knowledge, and often lectured before fellow architects and students. Speaking at the Boston Architectural Club, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and for other professional groups, he shared ideas and demonstrated different drawing techniques. Reprinting some of his lectures in The Technology Architectural Review, the magazine of the M.I.T.’s Architectural Society, Emerson’s methodologies were recorded and spread among wider audiences. He encouraged students to draw often, and think carefully about materials, shadows, and masses. Noting there is not often time for “elaborate mechanical perspective drawings,” Emerson encouraged young architects to be familiar with rendering materials and to be ready to draw at any moment. There is “almost hourly need of… freehand representations,” he claimed.

To illustrate his points, Emerson sometimes drew as he spoke, and examples from his M.I.T. lectures were reprinted in their magazine. Sketches made with pencil, reed pen, and brush showcase Emerson’s skills as a freehand renderer, while a drawing executed with toothpicks dipped in ink showed his ability to improvise with less common materials as well.

Courtesy of the Boston Athenæum

In addition to mentoring and teaching students and young professionals, Emerson’s lectures also influenced older and more established architects. A drawing by Robert Swain Peabody, partner in the firm of Peabody & Stearns, shows his interest in Emerson’s characteristic designs and drawing styles.

Memorial Library, Boston Architectural College

Labeled “After W.R.E.”, the full context of Peabody’s pencil drawing is not yet clear, but it relates to an unlocated Emerson pastel (a copy of which is included below) and may have been produced as part of a class or lecture on architectural rendering

Though details of Emerson’s office remain largely unknown, many who spent time working and learning from W. Ralph Emerson enjoyed successful careers in architecture. Charles Rich wrote fondly of his time working as a draftsman and recalled lunches at a nearby restaurant: “[S]ometimes Mr. Emerson went with us, and beguiled the time with pencil and pad which soon become luminous with sketches in soft pencil, pen or -yes, a toothpick and bottle of ink – it mattered not what. Fanciful sketches, towers, odd gables, chimneys, the study of the day perchance, from all points of view… I wager not an Emerson office boy who reads this, but in those days possessed a score or more of them, eagerly seized after they were drawn and cast aside.” Rich become a partner in the firm of Lamb & Rich, and designed shingled country houses for individuals including Theodore Roosevelt, but he was one of many who spent time in the office W. Ralph Emerson, and who carried Emerson’s teachings and legacy far beyond Boston.

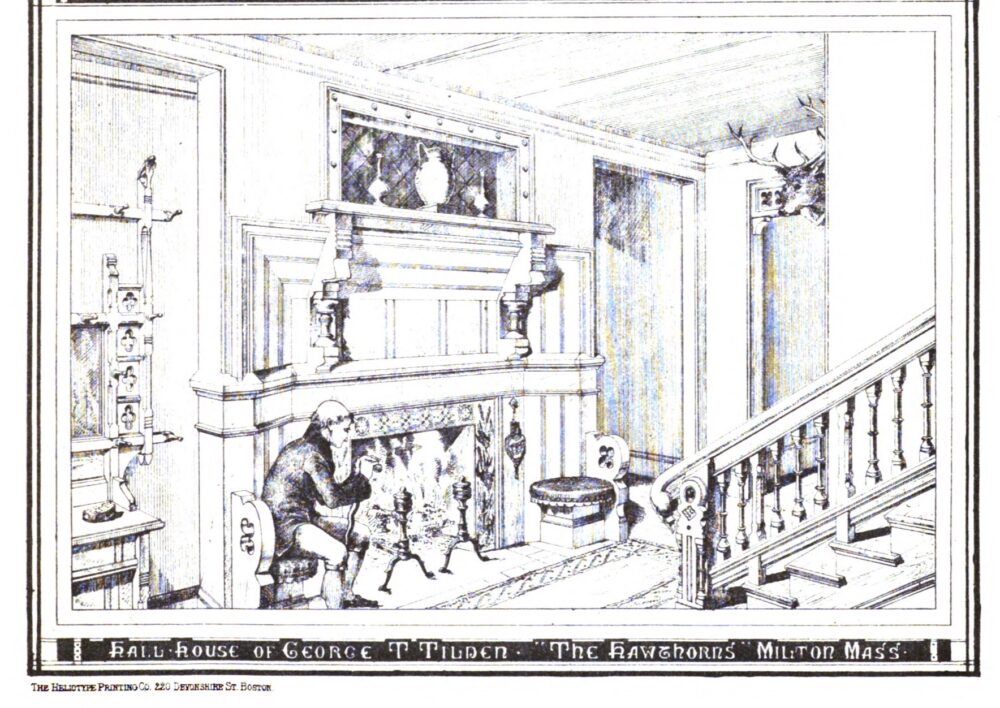

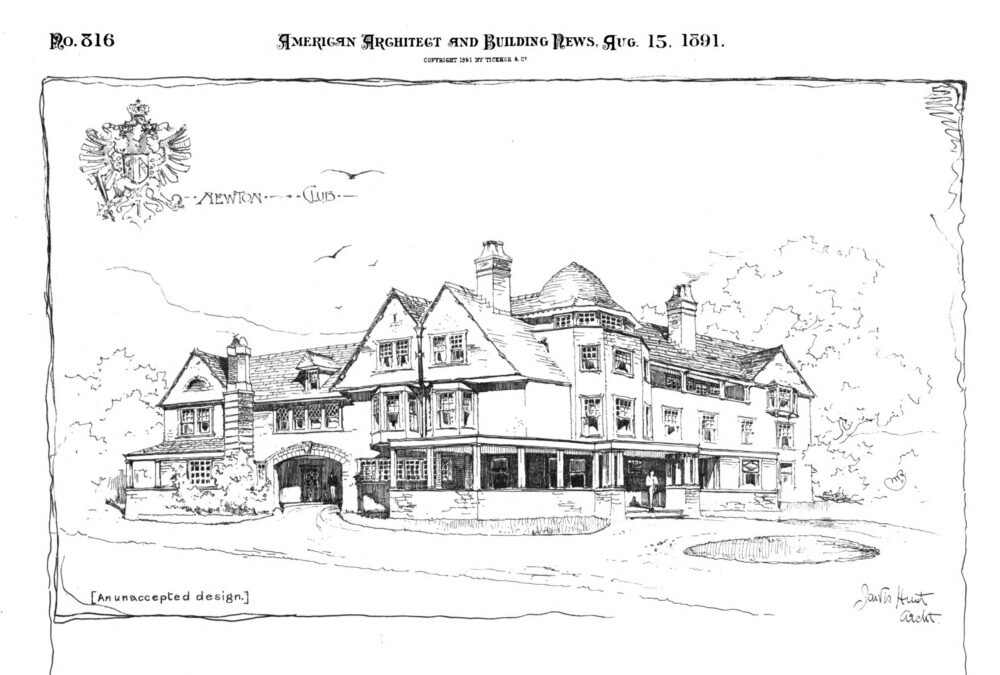

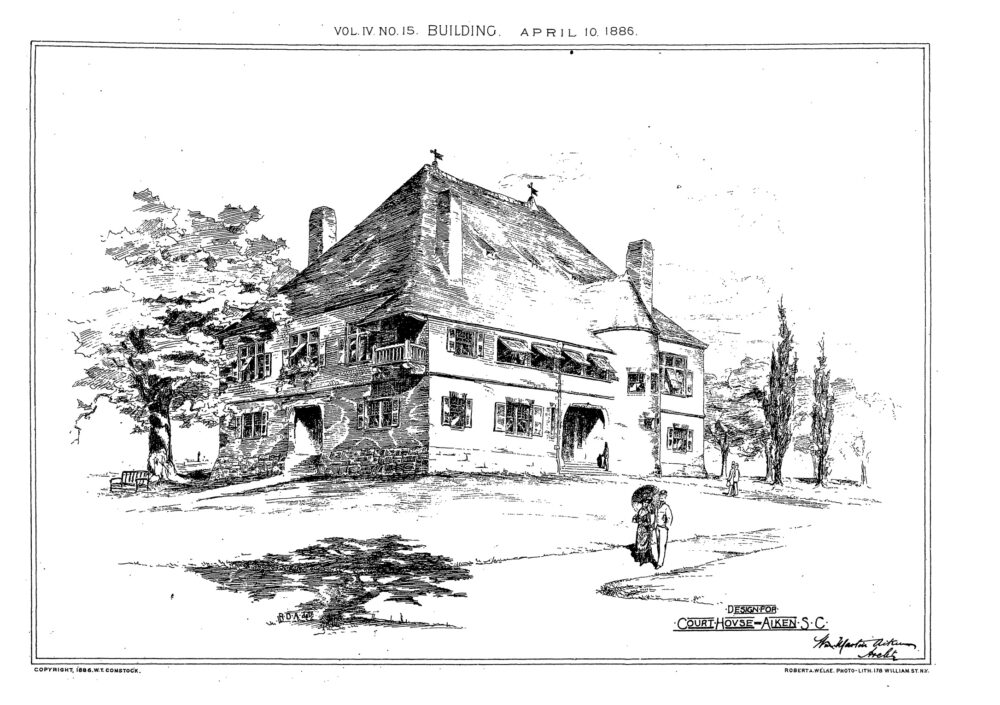

A selection of designs by individuals who worked in Emerson’s office: George Tilden, Lamb & Rich (Charles A. Rich), W.A. Norris,

Jarvis Hunt, William Aiken, Albert W. Cobb

Those known to have worked in the office of W. Ralph Emerson include:

- William Martin Aitken, circa 1882-1884

- William E. Barry, 1860s

- Albert W. Cobb, mid-1880s

- Ralph L. Emerson, circa 1893-1898

- Edward Aubrey Hunt, early 1870s

- Jarvis Hunt, circa 1888-1890

- Westray Ladd, circa 1889

Francis Minot, circa 1880-1883 - W.H. Nichols, circa 1891-1902 (or longer)

- W.A. Norris, 1880s

- Charles A. Rich, 1875-1879

- Joseph L. Silsbee, circa 1870- circa 1872

- George T. Tilden, before 1869

- Alexander Trowbridge, circa 1890

- Frank Weston, 1866

- William E.C. Whitney – circa 1872-1877

- Frederick W.C. Wood – circa 1875 – 1908

revised 28 February 2024